by Lil Molteno (nee Sandeman)

Source: Chronicle of the Family, Vol. 1, No. 2, August 1913, pp. 32-4.

Introductory Note

Lil Sandeman had grown up in Scotland. As a young woman, she got the chance to take a 6,000 mile boat trip to the Cape in 1905. While there, she met the Karoo sheep farmer who became her husband. Wallace Molteno happened to be down in Cape Town on business. The two of them met and fell in love and were married a year or so later in 1907. Lil now found herself settling down on a remote Karoo farm over 300 miles from Cape Town, and in surroundings utterly unlike the grey-sky, rain-sodden Fifeshire she had known as a child.

On the farm, Kamferskraal, there were numerous coloured farm workers as well as domestic servants doing work in the house. But Lil and Wallace also employed one or two Scottish women to help out as nursemaid or governess with their four small children. A century ago, the colour of a person’s skin was already a dominant social marker in South Africa. But class was also a reality. And a few white servants did exist alongside their fellow black domestic workers. The story below is a moving glimpse into the human ties that could develop as they navigated the ambiguous terrain of colour and class.

Robert Molteno

I have been asked to write an account of Janet’s farewell party to the coloured people, but as there must be members of the family who have never heard of “Janet”, charming Scotch housemaid, I think it would be better to write a short sketch of the six years she spent at Kamfers Kraal, where she reigned, an empress in her own right, among the coloured people on this little corner of the veld….

Janet had been many years in the service of my parents when I was married, and she responded to my invitation to come to me in South Africa by return of post. It was a broiling February afternoon when she arrived at Nelspoort Station with the other Scotch maid who accompanied her and I shall never forget her happy beaming face as she jumped out of the train, holding out both hands and saying “why, ye’ve no changed a wee bittie, Miss Lil”, or her approval of Wallace — when seeing him for the first time, she murmured in an ecstatic aside “Eh, but you’ve got a bonnie man”. I felt I need no longer yearn for my native land, as Scotland had come to me.

The old Kamferskraal farmhouse, a fragment still standing today

She walked into this house as if it stood in Fifeshire and took up her duties in the most matter of fact manner. When I asked her if she felt homesick, she always replied “I canna think I’m no in Scotland” and for six years she showed an example of untiring energy, of unfailing cheerfulness and unremitting hard work and everyone, from the Baas[1] to the smallest coloured child, felt the influence of her charming personality. Before a month had passed she knew every man and woman on the farm and all about them, the names and probable age of every child. (The ages of the Hottentot babies are generally reckoned from “the year the weir broke”, “the drought before last” or “the cold rain that killed the goats” etc. etc.) I don’t think in any part of South Africa there can be a more idle set of women (with a few bright exceptions) than the Hottentot women of the Karoo. Their idea of misery a day’s work, their idea of bliss to sleep in the sun, they will see their mistress slave from morning till night at all sorts of menial tasks and not raise a finger to help her unless compelled to do so. It came as a revelation to them to see two neat, nice-looking English girls at work from morning till night, cooking, sweeping, dusting, washing, or ironing, and singing at their work. By degrees they drew near to the kitchen door with voluntary offers of assistance and, after the first few months, there was no longer any dearth of female labour, they competed for the honour of helping in the kitchen, while the garden “boy” or the groom would be found scrubbing a floor or doing anything he could to help “Miss Janie” instead of attending to his own duties. It was to “Miss Janie” they brought their cut fingers to be dressed, their sick babies to be doctored, and their joys and sorrows to be shared and sympathised with.

But it was not only the human population that had Janet’s love and care. It was she who looked after the poultry, who supported and adored a whole regiment of cats, and who had various pets of her own from puppies to meerkats. One cold morning in April Wallace brought her a little half dead lamb from the kraals, telling her that if she could rear it, she could keep it. And Janet tended it with the greatest love, feeding it from a bottle, until in a surprisingly short time it grew into a sheep of vast proportions. It led a glorious life, grazing about near the house, nibbling pepper trees and geraniums and anything it particularly should not have eaten, and following its mistress about like a pet dog as well as always accompanying the procession of babies and prams on their daily walk. It is all very well to rhapsodise about a pet lamb but when the lamb becomes an enormous merino sheep, it has its drawbacks. Awful crashes were often heard as the lamb wrecked the kitchen in its playful gambols. But the crisis was reached when one afternoon Janet brought in the tea and left the door open behind her. In a moment the lamb bounded into the drawing room upsetting chairs, photographs and tables and breaking up the happy home. The Ou Baas arose in wrath and condemned the unlucky lamb to eternal banishment with one of the flocks.

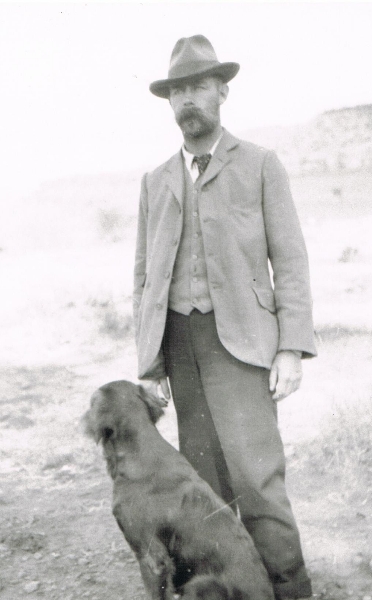

Wallace Molteno, Karoo farmer, c. 1900

Then followed several strenuous mornings spent in trying to chase the lamb away with any flock of sheep that happened to be leaving the kraals for the veld. The lamb refused to leave its mistress and tired out its pursuers.

Finally it had to be conveyed in a scotch cart and deposited with a flock five miles from the house. Terrible rumours reached Janet that her lamb was becoming pale and emaciated, refusing to graze with the sheep and pining for its mistress, and one Sunday a cart was inspanned and Janet driven in state to visit her lamb. She returned happier in her mind, having arranged with the shepherd to board the lamb in his house together with his six children, some scraggy fowls and a mongrel dog. There the lamb lived happily enough, apparently grazing on soap, candles and boxes of matches, to judge by the shepherd’s bill brought monthly to Janet for settlement, to replace his destroyed property.

How can I write of the ultimate fate of this pampered pet? Words fail me! When Janet left for Scotland she said nothing about her lamb and we supposed she had given it away, until the day after she sailed a skirmish was heard and round the house bounded “Janet’s lamb”. It had come to the house with the flock and was searching for its mistress. Then the Baas uttered awful imprecations and swore that there be an end to sentiment. The purchase money was despatched by cheque to Janet and no one asked any more questions and forebore to remark on the ultra excellence of the mutton for several days to come!!

I wish I could say that Janet’s only sorrow was the homesickness of her lamb during her six years here. But alas! It was inevitable that such a domestic treasure should not lie hid, even in the Great Karoo and a gallant police trooper rode up one day with flashing buttons and jingling spurs and laid siege to the heart of Janet. He was sent away almost immediately after their engagement to Mafeking and they kept up a correspondence for nearly three years. Then she heard from another that he was paying attentions elsewhere and realized that he had loved and ridden away. She wrote and broke off her engagement. She was never quite the same again though she stoutly declared “I’ll no break my heart for a man.” Her health broke down, her spirits waned and longing for her native heath assailed her. And so it was arranged that she should return to Scotland.

She asked my permission to give a farewell party to her friends, the coloured people, and I was only too glad she should do so and to provide the ingredients for a feast. With her own hands she baked all the bread and five hundred cakes, and with her own money bought oranges and quantities of sweets. The word was sent round that Janet would give a ball in the new wagon shed on the evening before she left and the news spread far and wide, so that when the evening came a hundred and twenty adults appeared and countless children although there are only forty grown up men and women on this farm and seventy children.

Farm worker (at Kathleen Murray’s farm, not at Nelspoort), c. 1920s

It was altogether a very grand party. The young men resplendent in fancy ties and new felt hats rakishly cocked the belles in coloured print skirts and blouses and new striped doeks round their heads — most of the young women dancing with babies securely tied on their backs, their woolly black little heads wobbling in the most alarming manner in time to the music. There were two bands consisting of banjos and concertinas, and the gramophone played at intervals, and a magic lantern entertainment (notable chiefly for its smell of paraffin) in a corner of the shed for the children. The tea was a great success, coffee being served in bedroom jugs and trays heaped high with cakes, and bread and jam. There was no silly bashfulness about Janet’s guests. They ate until everything was finished, tying up what they absolutely couldn’t consume in coloured handkerchiefs.

It was really touching to see the people’s devotion to Janet and the farewell they took of her. Nearly everyone had a present of some sort for her. One woman brought her a dozen eggs, another a fowl cooked for the journey. A young girl gave her a rhubarb tart (“and please, Miss Janie must give me back the dish”). And a shepherd contributed a live goat, a somewhat embarrassing attention! However the Baas with a rueful countenance, as he detests Boer goats, bought it from the shepherd who gave Janet all the purchase money, thus solving the problem. At 12 p.m. Janet took her leave and left her guests to dance till daybreak. People are apt to say that these Hottentots are hopelessly ungrateful and callous, but no one witnessing their farewell of their beloved “Miss Janie” could call them callous; it was with tears, with hearty handshakes, with blessings and with ringing cheers that they said goodbye to this simple-hearted kindly girl who had been their guide, philosopher and friend for the six years she had lived among them. And so she has gone from among us, away from the sunshine, the great wild veld, to the grey stone villages, the dour climate of her native land, and the Karoo knows her no more; but the coloured population, at least, will never forget their dear “Miss Janie”.

[1] Baas is the Afrikaner word for Master or Boss. Here it refers, as does Oubaas, to Wallace.