by Dr Charles Murray

Source: Chronicle of the Family, Vol 2, No 2, April 1914.

Dr Charles Murray, Royal Navy surgeon, 1870s

Introduction

This is the dramatic story of the unexpected capsizing in a storm of the Royal Navy’s most modern warship in 1870. Dr Charles Murray (he later married Caroline Molteno and had a large family) was a very young ship’s surgeon at the time. Born in 1848, he had grown up in Ireland. Although not from a wealthy background, he and his brother had both qualified as doctors in Dublin. Medical training, however, was not a lengthy affair in those days and by 1870, aged only 22, he was already serving on HMS Monarch. This ship, like HMS Captain, was part sailing, part steamship, but had been built to a very different design. They were both taking part in an exercise of the Channel and Mediterranean fleets off the northwest tip of Spain near Cape Finisterre. By chance, Dr Murray was witness to the tragedy that took place on the night of 6 September 1870 (he misremembers the year as 1869). An excellent storyteller, he relates the tragedy of what happened.

The significance of the story is that HMS Captain was the first attempt by the Royal Navy to adapt largescale warships to the age of steam as well as mounting much heavier guns with – for the first time – a 360° field of fire. This involved building a hugely heavy ship (nearly 8,000 tons) and with a rotating steel turret on the deck. But because the triple expansion steam engine had not yet been invented, steam propulsion was still inefficient and unreliable (see http://www.cityofart.net/bship/captain.htm). The ship had therefore also to be a fully fledged sailing vessel, but with its masts mounted on the upper hurricane deck while the turret was situated on a lower deck open to the sea. Further errors took place during construction. These increased the ship’s weight, and resulted in too low a freeboard (only 6 ½ feet) and too high a centre of gravity. The dramatic political story of the ship’s construction is told in Wikipedia at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Captain_(1869)

Robert Molteno

25 July 2012

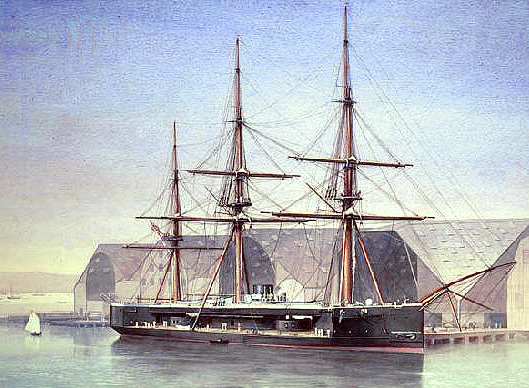

HMS Captain, c. 1870 — a water-colour

HMS Captain in the year 1869 was the very latest design in naval architecture and was looked upon as the greatest triumph in the shape of a sea-going battleship. Be that as it may, I have reason to remember her well, inasmuch as I was surgeon to her sister ship, HMS Monarch. Doubtless my reader may smile at such a reason, apparently about as good as that given by the Irish recruit were obliged to join the 99th Regiment, and who, on being told that was impossible, said: “wWell, put me in the 100th.” When asked “Why?”, he replied, “Sure, my brother’s in the 99th and, bedad, I’ll be near him anyhow.”

Well, the Monarch was frequently near the Captain. The Monarchs and Captains often contended in friendly rivalry. Of their officers, one at least, Mr Leonard Childers, son of the First Lord of the Admiralty, had changed ships. Both were turret ships, and were in those days the last word in naval construction, just as the Super Dreadnought is now. Both ships were under trial in the gale of wind off Finisterre, in which the Captain was lost. I remember as we steamed out of Gibraltar on the eve of that fateful day, how the Captain trained her guns on us as we steamed past to take up our position straight ahead. It was a weird sight to see her guns following us so as to demonstrate clearly her power of fore and aft fire. The Monarch replied in the same fashion, and it was fascinating to see the gaping mouths of the 25-ton guns of each ship apparently following automatically every movement of her rival. Never before had two ships provided amongst sailor men such topics of heated discussion as to their respective merits. In those days some of England’s “wooden walls” were still afloat – the fine frigates Immortalite and Narcissus and the grand old two-decker, the Donegal. It can be easily imagined how the old saltwater school looked askance at the newfangled monstrosity called a battleship, with whose advent the poetry of the sea well nigh disappeared.

Ships of this kind were present at the time I write of, and battled through the gale. Indeed, to them, handled as they were by officers and men who were past-masters in the art of sailing, a gale of wind mattered not; but to the newfangled monster it was quite another thing. New things are not always popular. At the time of the Crimean War, the story is told of Admiral Dundas who was much embarrassed by the presence, in his fleet, of HMS Argus, a steam paddleship. She was always getting out of her station. On the fleet going into action off Sebastopol, it was reported to him that the Argus did not keep station. He replied: “Oh, take the dammed wriggling thing out of the way”. Well, to some extent, that expresses the feeling held by some of the old sea dogs concerning the Captain. Many an argument have I heard as to whether she was safe in bad weather, or whether Davy Jones’ locker awaited her. No doubt it was only the talk of plain sailor men, but events proved that sometimes wisdom is found where least looked for.

The idea of constructing sea-going turret ships was due to Capt Cowper Coles, who from the date of the Russian war had advocated the mounting of guns in turrets. Finally, when the idea was adopted, it took two years to build the Captain and she was launched on 27 March 1869. The some months she served in the Channel Squadron and was mainly occupied in undergoing a series of trials to test her sea-going qualities. In the month of May 1869 [actually 1870], when with the Channel fleet off Finisterre she experienced bad weather, her behaviour was reported as “entirely satisfactory and worthy of all confidence, while her fighting capabilities were remarkably good”. Evidently the Admiralty thought that now the time had come when more extended work might be allotted to her, for she was ordered to join the Channel Fleet at Gibraltar, and it was while serving with it that disaster overtook her.

In August 1869 [actually 1870], the Channel and Mediterranean Fleets had orders to rendezvous at Gibraltar.

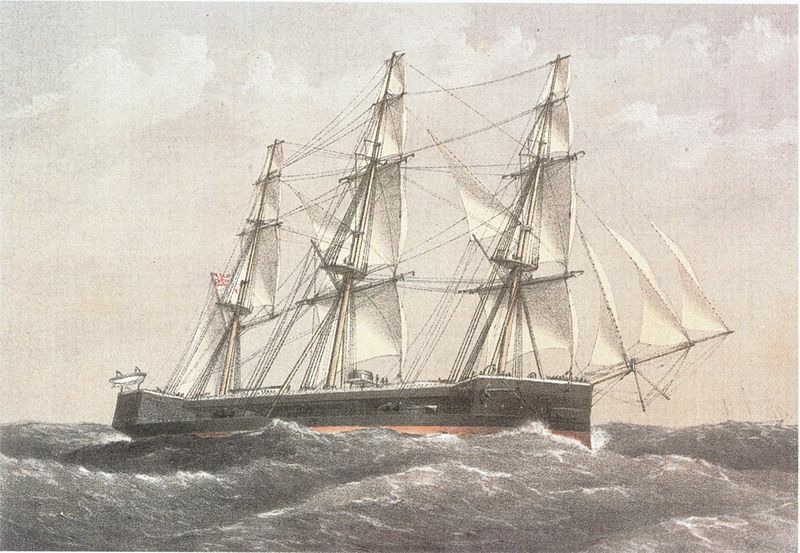

HMS Captain, a painting by Captain William Mitchell, April 1870

On 2 September they sailed thence for their respective destinations, but, before separating, certain joint manoeuvres by the combined Fleets took place off Finisterre on 6 September. About 32 sale of the line of different classes took part. Various sailing and steam tactics were tried, with screws connected and disconnected. What a glorious sight it was to see go by, under sail only, the old-fashioned but magnificent frigates like the Immortalite and the bluff old two-decker, the Donegal, followed by their modern sisters , the Inconstant and the Volage, the grim Ironclads doing their best, under sail, but in that test hopelessly out of it. Amongst the latter with the latest inventions in the shape of the Monarch and Captain, matched against each other, and what joy reigned in the hearts of the “Monarchs” when they outdid their rival on some point or other, and how contemptuously they looked upon some of the other Ironclads lumbering along behind, but doing their best to “save their face”.

But what of the weather all this time? The morning was dull and threatening. At 10 a.m. a heavy sea was getting up, and the wind had settled into a stiff breeze. The 32 ships were all on the alert, obeying signals from the flagship, and so the merry contest went on between the wind and sea, Britannia endeavouring to “rule the waves” according to the orders of the Commander-in-Chief of the combined Squadrons.

During the forenoon the Admiral went on board the Captain and it was rumoured that he remarked, on leaving, that he was “jolly glad” to be on board his own ship once more.

In the meantime the wind and sea increased, the weather became more threatening, but still the Fleets continued manoeuvring. Towards four o’clock in the afternoon the flagship signalled “Shorten sail”, “Get up steam”. In other words, “prepare for bad weather”. Well, bad weather we did get with a vengeance. About 9 p.m. it was blowing a stiff gale, with a heavy sea running; the combined Fleet was scattered, and only here and there a distant light could be seen. Our ship, the Monarch, had made ready for the storm – all sails taken in, the topsail yards lowered, the top gallant and royal yards down, steam up, all her boilers ready, her movable sides lowered so as to allow the seas to wash freely inboard and outboard, her turrets closed up and the guns tarpaulined.

In fact, she was then much in the condition in which she would have been if going into action – prepared for action, and into action she did go that night.

About midnight the gale raged fiercely, the good old Monarch groaned and kicked about and quivered as the heavy seas struck her, each blow being followed by a venomous hissing sound as the water surged past her turrets, along her decks, and swirled overboard.

At 12 o’clock I awoke and curious to see what was going on, went up the hatch and peered out, holding on tight. What a sight it was! The good ship kept her head to the sea; I could see her huge black hull rising as she climbed the oncoming wave, sometimes gaining the crest, then sliding down again into the black yawning gulf. Now and again the sea struck her, ere she reached the summit, drenching her with spray. Then she shook herself, and quivered and vibrated under the shock like a living thing, as the water hissed along her decks. The wind roared through the rigging, the sky was black as ink, and seemed to press the ship downwards into the abyss she tried to avoid. It must then have been about ten minutes past twelve when, as I stood in the hatchway, I heard the engine room bell ring, and from the bridge, out of pitch darkness, came the voice of Captain Commerell (afterwards Sir Edward Commerell V.C.) in sharp and decisive tone, giving the order to go “full steam ahead”. Gallantly the brave ship answered the call and, through all the uproar of hell let loose, held on her way. For some time I stood there listening, wondering how we it all would end, and then, as it was not my job, I went below and fell asleep. At six bells I turned out, visited the sick and then went on deck. The gale was over, the sun shone out, there was little wind. The Fleet was scattered, not a ship in the sight, but, strange to say, not far from us there lay, hove-to, a little bark-rigged trader. There she lay, bobbing and ducking to the sea. She had weathered the gale, and seemed to be taking matters quite easily. Presently she braced her yards, shook out the sails and resumed her course. What a contrast to the weary giant battleship!

I went down to the Wardroom just before breakfast, and there I found the Paymaster and the Staff Surgeon in close confab. They looked troubled, and the old Paymaster positively ill. I said: “What’s the matter?” He replied: “Well, I have had a bad night and a horrible dream. I dreamt we had a terrific storm and, in the blackness and turmoil of it all, I saw the Captain turn right over. I saw her lying bottom upwards, and heard the most awful roar, mingled with shouts of her men as she disappeared. Then I awoke, and after that I spent the night tossing about.” He looked shaken and ill. “Oh,” I said, “we did have a gale and in your sleep you heard it.” At that moment the Lieutenant of the Morning Watch, who had just been relieved, came in and said: “Hullo, you landlubbers, how goes it? Have you left anything to eat? The Captain’s missing!”

We finished our breakfast in silence. It was easy to see that gloomy foreboding occupied our thoughts. After eight bells the look-out man reported: “Sail in sight”; later on reported “Flagship”. Now the signal to the Fleet was made “Resume stations”, and gradually as the day wore on, all ships reported save one. Then came the signal “Captain missing”, followed by the order: “Fleet to scatter and search”. However no trace of her could be found. During the day the Helicon, a dispatch boat from Gibraltar to England, passed us. She signalled that she had passed a boat, bottom-up, and further on, two dead bodies. Anxiety was now written on every face, and on all sides was heard anxious questioning. Had the Captain come to grief? Or had she sheltered in some bay? Some said: “She is just as good a sea boat as any of us.” Others shook their heads and feared the worst. As the day wore on some wreckage, a part of the Captain’s bowsprit, was found and, tied on to it, a sailor’s long silk scarf. Even then some of us still argued, “What of that, very likely it snapped off, thus carrying off the man who had evidently tried to lash himself to it”. Towards evening was found a piece of panelling, painted in ebony and gold. It was recognised as a piece of the lining of Captain Burgoyne’s cabin, and as this cabin was below the waterline, it indicated only too surely the doom of the ill-fated vessel. The next morning, the Admiral signalled to the Fleet to return to headquarters. Accordingly the Mediterranean and Channel Fleets return to their respective stations, leaving HMS Monarch under Capt Commerell to remain off the Spanish coast to search for any further trace of the Captain.

Next day we drew closer to the shore, a steam pinnace was lowered, and we proceeded to reconnoitre. When off Corcubion Bay, we met a Spanish fishing boat which told us that some shipwrecked sailors had come ashore in a boat and were at present in the town of Corcubion. This was good news. Captain Commerell sent immediately a ship’s cutter, of which I was one of the crew, to give help to the men. I remember how excited we were to be the first to find the survivors, and I blessed my lucky star that I was the surgeon, as it gave me a chance of being amongst those chosen. Well, the cutter made sail and stood right in to Corcubion Bay. It was the first time I had ever been in a small boat in the open sea. How different it was to harbour, or even roadstead work, to which I was accustomed. There was a heavy swell on, and as the little boat held her way under sail, we soon lost sight of the ship and at times saw nothing but the sky above and the sea below. As we were about to enter the Bay, we passed through an immense shoal of porpoises. Only once before had I seen such a shoal, or been in their midst, and that was off Prince Edward Island; but never before had I seen them hang so persistently round a boat. There was something almost uncanny about it. Even our cutter’s crew sat thoughtfully gazing at the extraordinary sight. Towards evening we reached the little town of Corcubion and there are, at the landing place, came to meet us the 18 sole survivors of the Captain.

At last the moment had arrived when we should hear, from their own lips, their story, and that night, seated round the fire in the house allotted to us by the Alcalde of the town, we listened to our shipwrecked comrades’ thrilling tale.

Mr James May, her gunner, told us how he awoke at midnight and had felt the ship labouring heavily. Knowing that she was a newfangled craft, with her heavy guns in turrets and that her 600 lb.shot and shell were in the racks, he felt anxious as to their security. Accordingly he got up and took up his lantern to have a look round. Just then a heavy sea struck the ship and she reeled over tremendously. At that moment he put his lantern down and ran up into the turret. There, as he squeezed his body through the manhole, he was immediately washed overboard by a heavy sea. When he came to the surface, he espied the pinnace floating bottom upwards towards him with a few men clinging to her, amongst whom was Captain Burgoyne, and he succeeded in reaching them. Soon they saw a large black object coming along on the crest of a wave. This proved to be the launch with some men in her. As she passed by, he called to Capt Burgoyne to jump. They all jumped. Some managed to reach her and were dragged in, but some failed, and amongst them was Capt Burgoyne. Now began a fierce struggle to keep the boat afloat, during which time they picked up some more men, 18 in all.

The history of how the launch got afloat we heard from another of the survivors. It was a very large launch and was stowed on the Captain’s spar deck, resting in great clutches to which it was firmly lashed.Fitted with mast, oars etc, and covered with stout tarpaulin, it looked one firm solid mass. The narrator told us how, on his being relieved from the first watch, he had been so much alarmed at the condition of the ship that he hesitated to go below, and it occurred to him to cut the lashings of the boat and get into her. He said that he realised that in doing this he was liable to be tried by court martial, but the circumstances seemed to him to justify the risk. No sooner had he accomplished this, and got into the boat, than a heavy struck the unfortunate ship. She turned right over and the launch was flung into the sea. He struggled to his feet and eventually succeeded in picking up one by one the 18 men that were saved. For a few moments the ship could be seen bottom upwards, then, evidently, turrets and boilers fell out. There was a horrific roar of steam, accompanied by the cries of the men; then a final plunge and she disappeared under the waves. So perished the Captain with her gallant crew of 490 officers and men, amongst whom, strange to say, was Capt Cowper Coles himself [the designer of the new ship]. From the time she turned bottom up to the time she disappeared, was thought to be about 5 minutes.

And now the launch began its fierce struggle for life. It was crowded with rough odds and ends, as well as a gig. Mr May, was the only Officer left alive, took command. First, with great difficulty, they cast the gig overboard; then an attempt was made to bring her head to wind, but the force of the wind and sea was so great that the man in the bows was washed away, and the oars were blown out of the men’s hands and sent flying through the air like chaff. Seeing it was a hopeless task to attempt to keep her head to the wind, Mr May determined to let her run before it, and so she drifted along four hours, rolling and pitching, now tossed on the crest of a wave, now lying still in the trough, at times partly swamped; the roaring of the waves and wind shutting out all other sounds. During this time a large frigate passed without seeing them, thus adding a further note of despair to the horrors they were undergoing. Three of their number lay, apparently dying, in the bottom of the boat. However, the remainder stuck to their work of baling, trimming and steering her, and so the ghostly hours of darkness and storm wore on. Towards daybreak the wind abated, the sun rose, and they found themselves off Cape Finisterre with a fair wind behind them. Then Mr May decided to run for Corcubion Bay, so by the help of their oars and by rigging up clothes and sail covers (sails there were none), they managed to reach the land about midday.

Such were the tales told us. Verily these men had passed through “the Valley of the Shadow of Death”, yet, as I scanned their weather-beaten faces, and saw them cheerful and undaunted, it was difficult to realise they had just undergone so terrible an ordeal.

Meantime Captain Commerell had ordered the Monarch to anchor close off the town. There she lay, undergoing already the usual “polish up” after her rough experience.

As yet, beyond these 18 survivors, no trace of the wreck had been found, but we had heard from the townspeople that there were one or two places along the coast where wreckage was sometimes cast up. Captain Commerell determined to visit these and formed a little expedition, consisting of himself, a lieutenant and myself, the surgeon. We were to ride mules and the Alcalde furnished us with two guides. Altogether we formed a party of five. Towards evening we reached a small town. Here we spent the night. Next day we went along the coast searching and making enquiry but no further trace of the wreck did we find, nor had any dead bodies been washed up. That part of the coast near Cape Finisterre is, in places, rugged and wild beyond description, precipices drop sheer down, and against them the sea fairly boils – enormous waves roll on crashing themselves against the cliffs, and the whole scene is one of awesome grandeur.

The next day, as there seemed to be no prospect of getting further information, Captain Commerell determined to return to Corcubion. The present sight it was to see the Monarch lying there at anchor, already the painting process had obliterated most of the traces of hard wear. Her snowy decks, her shining brass work, and above all the jolly sunburnt faces of our men, gave a welcome feeling of comfort and security after the storm and tragedy of the past few days.

Captain Commerell remained here a few more days, no doubt still hoping that some news from the distant coast villages might reach us.

On leaving Corcubion, we transferred the survivors to HMS Volage who took them back to England, the Monarch following at a more leisurely pace.